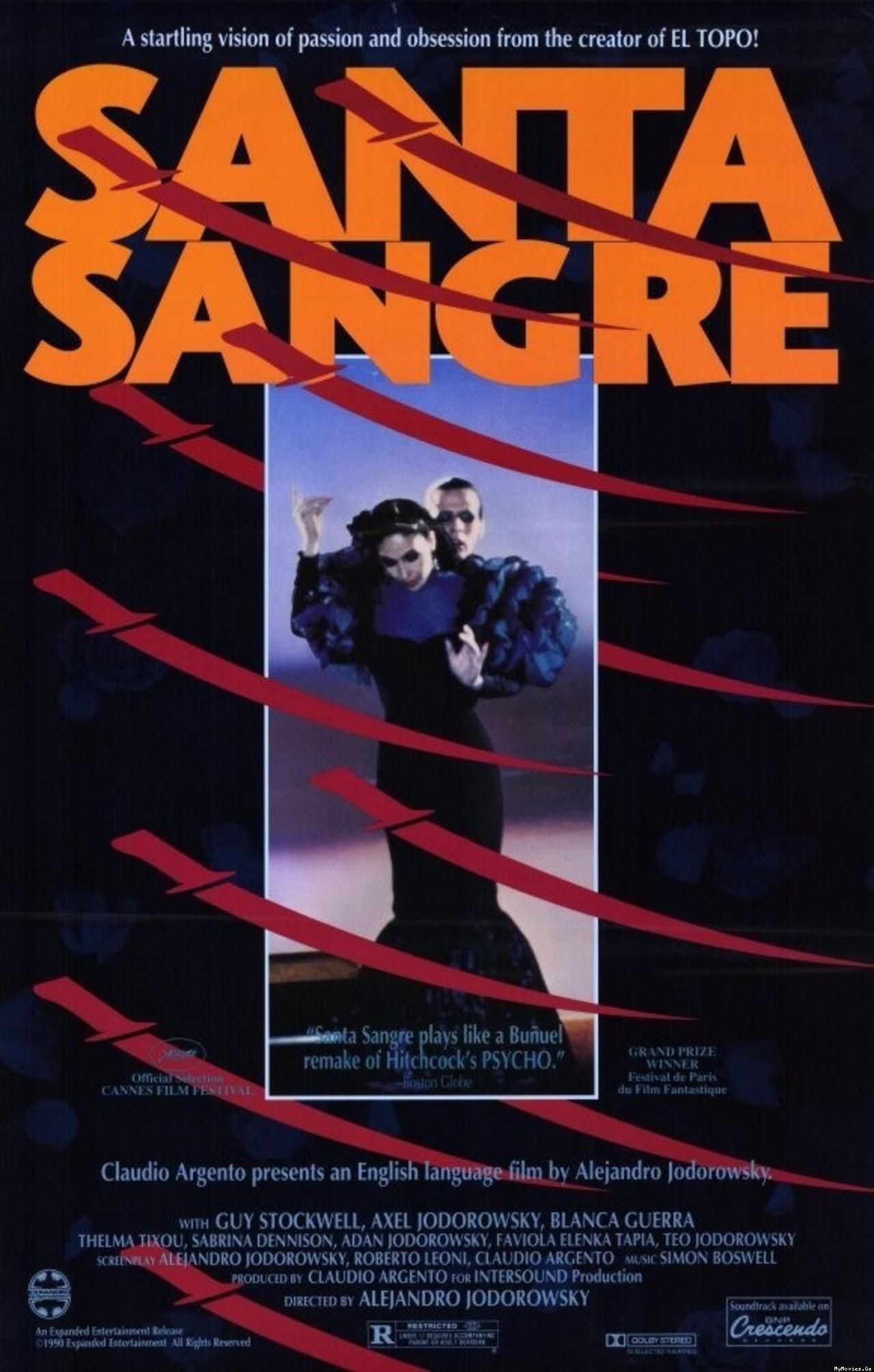

SANTA SANGRE

Surrealist masterpiece

Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1989, Mexico/Italy

123', DCP, English 2w/French subs

In the presence Stephen Sayadian

Violence

Alejandro Jodorowsky entered my life in 1972, when El Topo, John Lennon’s favorite film, became the first major Midnight Movie. I first saw it at Chicago’s Playboy Theater, at midnight, on LSD. To this day, some of the images haunt my dreams. Seventeen-years later, I saw Santa Sangre at LA’S Nuart Theater, this time without LSD. To this day, some of the images haunt my dreams. Turns out it was Jodorowsky, not the acid.

The following is from a 2003 review by Roger Ebert: To call Santa Sangre (1989) a horror film would be unjust to a film that exists outside all categories. But in addition to its deeper qualities, it is a horror film, one of the greatest, and after waiting patiently through countless Dead Teenager Movies, I am reminded by Alejandro Jodorowsky that true psychic horror is possible on the screen – horror, poetry, surrealism, psychological pain and wicked humor, all at once.

The story involves Fenix, the boy magician at the Circus Gringo, a shabby touring show in Mexico. Played by two Jodorowsky’s sons (Adan at about 8, Axel at about 20), Fenix is the child of the beautiful trapeze artist Conch (Blanca Guerra) and the bloated circus owner and knife-thrower Orgo (Guy Stockwell). Always at Fenix’s side is the dwarf Aladin, who acts as his assistant and moral support.

The little magician’s best friend is Alma. She is a deaf-mute mime, the daughter of the carnal Tattooed Woman, who works as the target for Orgo’s knives. One night when Concha is suspended above the circus ring by her hair, she sees Orgo caressing the Tattooed Lady and screams to be brough back to earth. n a rage, she surprises them in bed and throws acid on Orgo’s genitals. Bellowing with pain, he severs her arms with mighty thrusts of two knives. Then he kills himself, the acid having rendered him uninteresting to women tattooed and otherwise.

Concha’s mutilation is a cruel irony. She is the leader of a cult of women who worship a saint whose arms were cut off by rapists. Their church contains a pool of blood, no doubt suggesting menstrual fluid (Concha’s name is Mexican slang for the vagina); its members wear tunics with crossed, severed arms. When authorities arrive to bulldoze the church, there is a clash between the women and the police, and then a shouting match between Concha and the local monsignor, she screaming that the pool contains holy blood, he replying that it is red paint.

The bulldozing reveals the shabby construction of the church, mostly made of corrugated iron and possibly reflecting the film’s limited budget. If Jodorowsky’s funds were limited, however, his imagery and imagination are boundless, and this movie thrums with erotic and diabolical energy. Consider the scene where the circus elephant dies after hemorrhaging from its trunk. In a funeral both sad and funny, the beast’s great coffin is hauled by truck to a ravine and tipped over the edge – to the delight of wretched shanty-dwellers, who rip open the casket and throw bloody elephant meat to the crowd. An image like this is one of the reasons we go to the movies: It is logical, illogical, absurd, pathetic, and sublimely original.

For Alejandro Jodorowsky, all in a day’s work.

Stephen Sayadian

Paderewski

Paderewski